The Sad Tale of the Clipper Ship Wildfire

The Wildfire

In 1846 the Amesbury poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier wrote the poem, “The Ship-Builders,” one of a number of poems that celebrated the labor of those who were building a new nation. The poem praised the work of Amesbury men who were building the “greyhounds of the seas,” the great clipper ships of the day that would bring the goods of America to the world and the goods of the world to America. However, that poem also contained a warning. He wrote:

Speed on the ship! But let her bear

No merchandise of sin,

No groaning cargo of despair

Her roomy hold within;

No Lethean drug for Eastern lands,

Nor poison-draught for ours;

But honest fruits of toiling hands

And Nature's sun and showers.

John Greenleaf Whittier – 1846.

That stanza reflected Whittier’s concern that ships of the day were carrying slaves, the “…merchandise of sin” and a “cargo of despair.” The dispute over slavery was contributing to the division of his beloved country.

In 1853, six years after the publication of that poem, from the shipyard of Simon McKay, where the Powow River joins the Merrimack River, the clipper ship Wildfire was launched. Although built as a clipper she had the iconic square sails only on her first two masts and as such she was categorized as a “bark.”

“On March 31, 1853 the Amesbury Villager reported, ‘We learn that the new and beautiful clipper ship built at the yard of Mr. McKay, at Amesbury Ferry, will be launched on Wednesday next. As a specimen of skill in shipbuilding, combining speed, beauty of model and elegance of finish, she cannot be excelled by anything yet set afloat on the Merrimac. Such is the confidence of her builders in her sailing qualities that they will challenge the whole fleet of sailing vessels in New England to a trial of speed.’”

The Wildfire was built for Peter Hargous of the Hargous Brother’s Shipping Company of New York City. She was to sail the trade routes of the Mediterranean. Under Capt. Mosman she sailed from Boston May 13, 1853 arriving at Malta on June 8. She passed Gibraltar when 14 days out setting a new trans-Atlantic record. A letter from her captain says that, “… she is not only an excellent sea boat, but the swiftest vessel he ever saw. Her best days work was 306 geographical miles, she can ball 15 knots with ease.” He asserted that, “No vessel in the Mediterranean trade can begin to approach her in speed, and we know from personal inspection that she is well built and beautiful. “ She was built of oak and fastened with copper and iron fasteners. She had one main deck and a half-poop deck. Wildfire was listed at 338.3 tons with the following dimensions length 128 ft. 4 in. (on deck); breadth 27 ft. 4 in.; depth of hold 10 ft. 6 in. she drew 12 feet of water. Her lower hull was covered with metal sheathing in October of 1858 as protection from wood-boring marine worms.

She was one of many ships of her type built during that period for the California Gold Rush. Although the Wildfire never sailed the Gold Rush route her fate was tied to its demise when the Gold Rush ended in 1855. Overbuilding created a surplus of ships that drastically reduced their value. As a result the Hargous Brothers shipping company concentrated their efforts on the trade routes between New York, Havana, the Carib-bean Islands, New Orleans and southern Mexico.

The Wildfire was then sold to the slave trader Pierre LePage Pearce in 1859. Thus began her career as a “blackbirder,” as slave ships were called, carrying “a groaning cargo of despair.” Pearce was heavily involved in providing slaves for the booming Cuban sugar industry.

By 1859 when the Wildfire began her service in the slave trade the British and American governments had been actively trying to end the slave trade between Africa and the Americas for over 50 years. In 1807 Great Britain had outlawed the salve trade and rigorously enforced it’s antislavery policies. The American government followed suit in 1808. The British and American navies were particularly focused on the trade between the coast of West Africa and the Caribbean. Their efforts put a crimp in the supply line between West Africa and Cuba. This made a cargo of slaves extremely valuable in labor starved Cuba.

The Wildfire sailed from the port of New York on December 16, 1859 with a cargo of calicoes and other cotton goods, headed for St. Thomas, Danish West Indies under William Stanhope, Master. From there she sailed for the West coast of Africa.

Early in 1860 Pearce embarked 615 African slaves and set sail for Cuba. He would not finish that trip. The Wildfire was stopped and boarded by sailors from the USS Mohawk on April 26, 1860. Naval officials found 514 Africans, including 100 women, who had survived the trip up to that point. The Captain of the Wildfire, Philip Stanhope and her crew were arrested and charged.

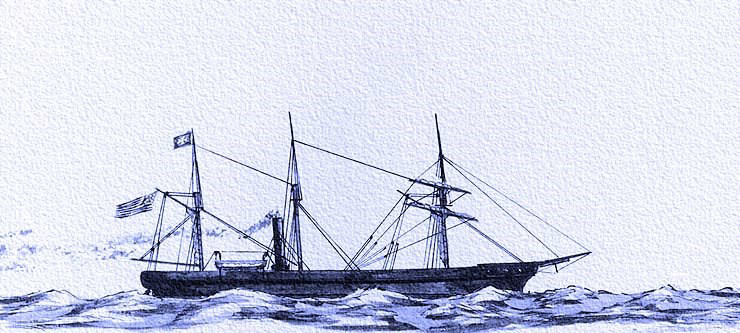

The USS Mohawk

May H. Stacey, of the US Steamer Crusader, visited the ship and wrote of the space constructed for the Africans, “ A glance on the slave deck was enough to fill the mind with indiscernible horror at the thought of what the poor creatures must have suffered in twenty eight days passage. The deck was constructed of rough un-planed planks and raised from the ships bottom about three feet leaving a space of about four feet in height and extending fore and aft.”

A depiction of how slaves were transported

Harper’s Weekly, an American political magazine based in New York City, from 1857 until 1916, published a lengthy article about the interception of the Wildfire along with a woodcut illustration of the deck of the ship with its “cargo of despair”.

Slaves aboard the Wildfire as portrayed by Harper’s Weekly

The Wildfire was seized under the Slave Trade Act of 1794 which prohibited making, loading, outfitting, equipping, or dispatching of any ship to be used in the trade of slaves, essentially limiting the trade to foreign ships, and the slave Trade Act of 1800 in which Congress outlawed U.S. citizens' investment in the trade, and the employment of U.S. citizens on foreign vessels involved in the trade. The Wildfire was condemned by Judge William Marvin and the ship was sold at public auction on May 5 1860, and the proceeds of $6,087.76 were split between the US Treasury and the crews of the Navy cruisers who captured it.

The Captain, Phillip Stanhope, and his crew were jailed at Key West, Florida. The Captain was freed on bail of $1000 and the arrested crewmen were also given bail of $450 each. Eventually, charges were brought against Captain Stanhope and the crew of the Wildfire but the Grand Jury in Key West found no true bill against them, thus a verdict of not guilty was rendered. Despite being caught red-handed, they were freed. Perhaps this was a commentary on the nature of the division in the country regarding the “peculiar institution” of slavery.

Gomez, Wallis & Company then purchased the Wildfire and had the hull sheathed with new metal in January of 1861. In February the ship was inspected at New York, and rated class “A2.” What became of the Wildfire after this apparent rehabilitation is not known.

The United States government contracted with the American Colonization Society to return the Africans to the country of Liberia, which had been founded with the support of the United States in 1830 to pro-vide liberated slaves a chance to start life anew as free people. By July of 1860 the surviving Africans were aboard ships bound for that country. Unfortunately 95 of the Africans from the Wildfire died before their re-patriation was possible.

Sources for this article:

Corey Malcom, Director of Archaeology, Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society, Inc. Key West, Florida and Lawrence B. Conyers, Ph.D. Geophysical Investigations, Inc. University of Denver, August, 2002© Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society, Inc., 2002.

The Terrible Transformation /pbs

Harper’s Weekly June 2 1860