Amesbury’s “Alliance,” from the American Revolution to the China Trade

By Paul Moscardini

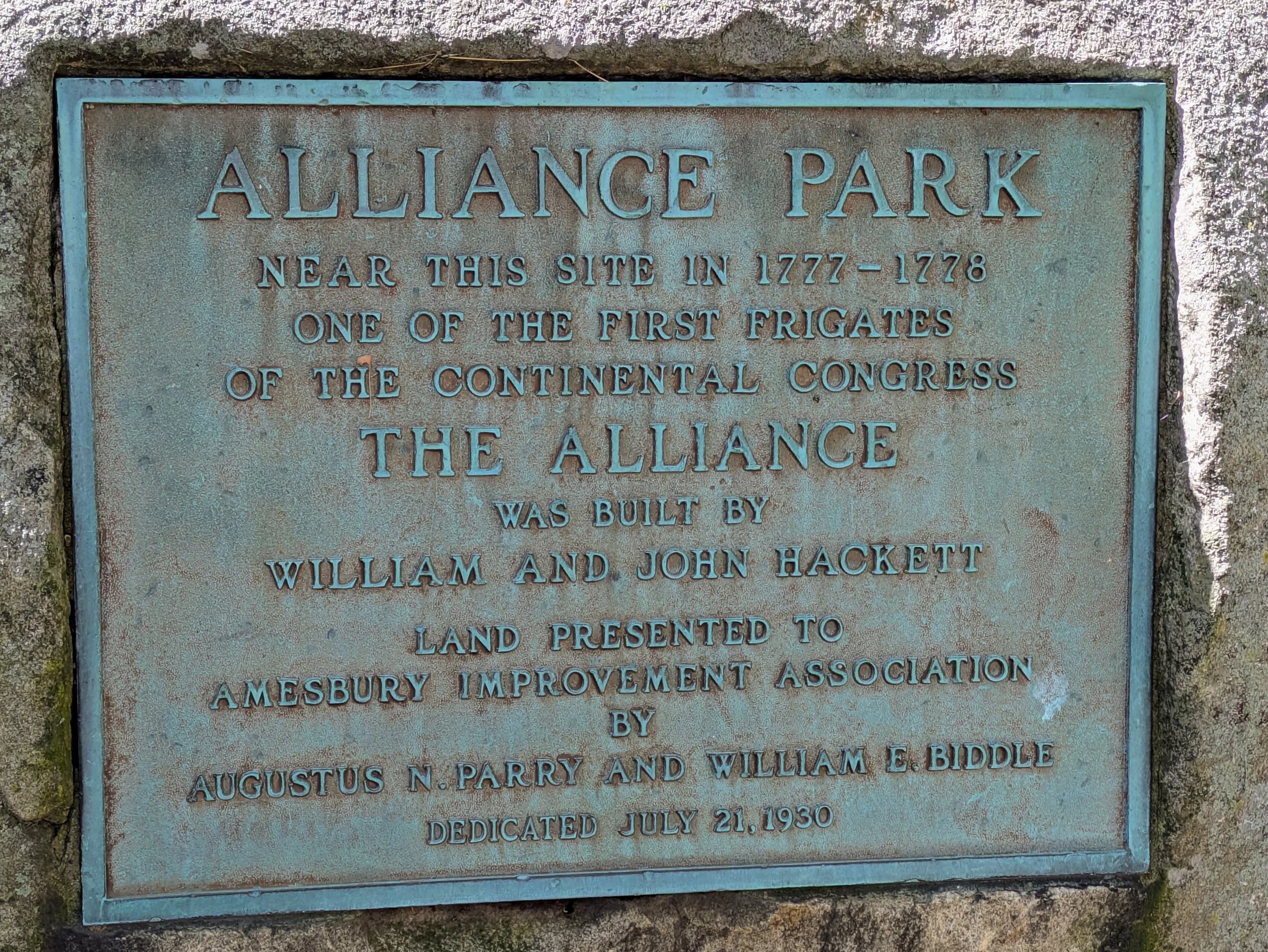

On April 28, 1778, the frigate Alliance was launched by William and John Hackett from the Merrimack River shipyard of Daniel Webster in what was then Salisbury, Massachusetts. Today that land is part of Amesbury and the ship built there is commemorated in the form of a plaque a short distance from Alliance Park at the site of the shipyard located between 357 and 363 Main Street where the Alliance was launched over 200 years ago.

The plaque at Alliance Park in Amesbury

A representation of a ship launched in the 18th century

Initially, she was to be named the Hancock but was renamed to honor the formal Treaty of Alliance between the governments of the United States and France signed in Paris on February 6, 1778. That Treaty was important to the ultimate success of Great Britain’s former colonies in their War of Independence.

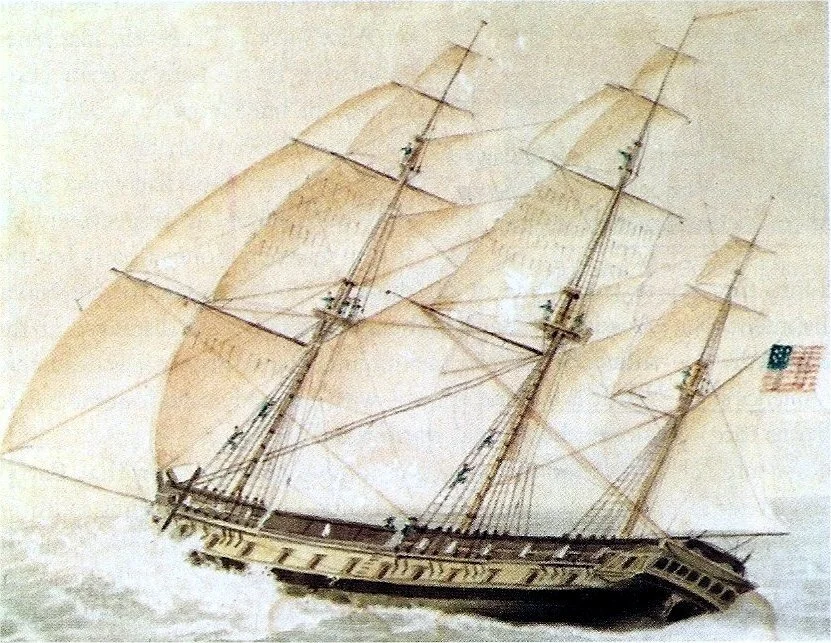

The Alliance was a 36-gun frigate. At the time of her construction a frigate was deemed to be a ship designed for speed and used for patrolling and escort duties. She would have a single, continuous gun deck carrying at least 28 guns. Below is a painting of the Alliance from the U. S. Naval Institute Archives. She had a displace-ment of 900 tons, was 151 feet long, with a beam of 36 feet and a depth of 12 feet 6 inches. She carried a crew of 300.

The Alliance under sail

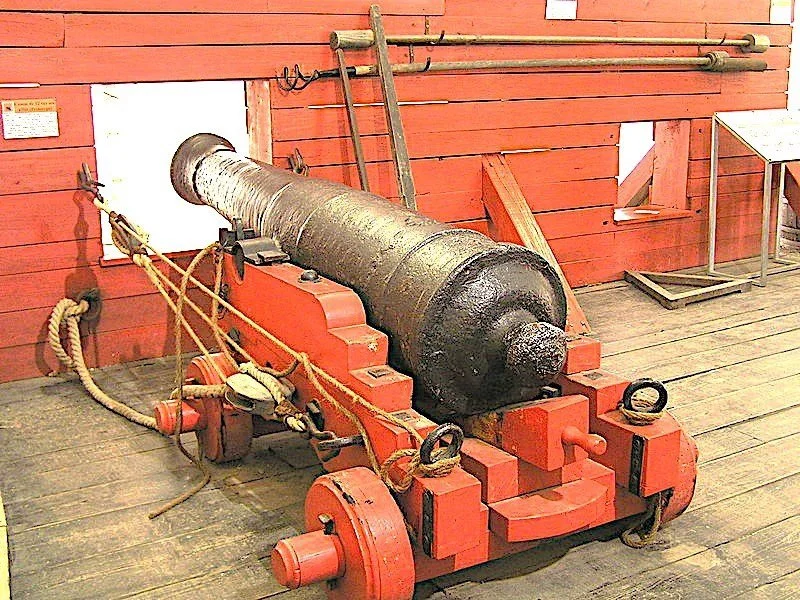

Her armament consisted of twenty-eight 12-pound smoothbore cannons and eight 9-pound smoothbores. A cannon of similar characteristics is shown below.

The Alliance was said to be the finest ship at that time to be built on this side of the Atlantic. Many years after the War of Independence John Adams recounted a con-versation with the Intendant of the French naval Base at Lorient, Monsieur Thevenard in which Adams suggested that American shipwrights were not the equals of those in Europe. Thevenard responded by saying that “ The frigate in which you came here [The Alliance] is equal to any in Europe…. And I assure you there is not in the King’s service, nor in the English Navy, a frigate so perfect and complete in materials or workmanship …… there is not in Europe a more perfect piece of naval architecture than your Alliance…”

Following her launching she was moved to Boston Harbor and fitted out. She was placed under the command of a former French naval officer Captain Pierre de Landais, a man described by some as an “adventurer,” with a checkered past who would create some problems as the war at sea evolved.

Captain Pierre de Landais

Landais, now in command of the Alliance, was ordered to France to transport the Marquis de Lafayette to petition the French King, Louis XVI for more aid for the colonists fight against the British. The Alliance departed Boston on January 14, 1779 bound for Brest, France.

Continental Frigate Allaince passing Boston lighthouse from sea. Painting by Matthew Parke

Captain Landais arrived in France on February 6th claiming to have put down a mutiny amongst his crew, which was said to be made up of former British and Irish sailors. On that journey the Alliance was credited with seizing 2 prizes, ships captured from the British whose value would be divided among the crew. Suspicious of his ac-count of events, Benjamin Franklin, America's envoy in France, attempted to remove him, writing "if I had 20 ships of war at my disposition, I should not give one of them to Captain Landais…” Despite that Landais re-mained in command. He was ordered by Franklin to join the command of Captain John Paul Jones.

Captain Jones was escorting merchant ships to France, protecting them from British seizure. In the course of that duty Landais and the Alliance collided with Jones’ ship the Bonhomme Richard, both ships being damaged as a result. Later that summer of 1779, Jones, in support of French plans to invade southern England, was to con-duct a diversionary raid in the north. It was during this operation that Landais behavior became non-cooperative and, one could argue, mutinous. Landais ignored his orders and instead of cooperating in an “alliance” with his American and French counterparts sailed independently in search of prizes. Things came to a head on September 23, 1779 at the Battle of Flamborough Head in which Jones’ ship engaged the British vessel Serapis. In the course of the battle the Alliance fired on Jones’ ship. Be-tween damage received during the battle and Landias’ unexplainable actions the Bonhomie Richard was too damaged to survive.

The Battle of Flamborough Head. The Bonhomme Richard battle the British ship Serapis as the Alliance stands by in the distance

Jones transferred his crew to the Serapis and abandoned the Bonhomme Richard to sink. Eventually Landais was relieved of command of the Alliance, but not accepting Franklin and Jones’ authority over him sailed for America hoping that the Continental Congress that had commissioned him would support is plea to remain in command. The journey did not go well. Landhais’ erratic behavior caused him to be removed from his command by Lieutenant James A. Degge. Later a court-martial relieved both Landais and Degge from naval service. In September of 1780 the command of the Alliance went to Captain John Barry often referred to as the “Father of the American Navy”.

Captain, later Commodore, John Barry

On February 11, 1781 the Alliance under the command of Captain Barry, the ship having been refitted and made ready for sea in Boston, was ordered to provide transport for Colonel John Lawrence to France as an “envoy extraordinary” to plead on behalf of General Washington for more aid. Also on Board was Thomas Paine, author of the treatise Common Sense, a pamphlet that Paine had written to promote among common people the idea of separation from Britain.

On her way home from her mission in France the Alliance under Barry’s command captured 4 prize ships, two merchantmen and two warships. She arrived in Boston on June 6, 1781.

While the Alliance was waiting for refitting, Lord Cornwallis, lead commander of British forces in America, surrendered his army at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, ending the war’s last major action on land, but not the war. Following her refitting it was decided to use the Alliance to carry the Marquis de Lafayette, who had completed his work in America with a major role in the Yorktown campaign to defeat Cornwallis, back to France.

Following his delivery of Lafayette back to France in January of 1782 Barry and the Alliance sailed into the Bay of Biscay in search of prizes, the taking of which could be used to pay for the exchange of American prisoners of war. That did not work out so the Alliance sailed for home on March 16, 1782, arriving at New London, Connecticut on May 13. Between May and October of that year Barry and the Alliance sailed the Atlantic seeking and taking a number of prizes. By October he was near the French coast so he put in to Groix Roads, France on the 17th of that month.

The Alliance got underway again on December 9, 1782 for the West Indies. There Captain Barry was given orders to sail to Havana to pick up a large quantity of gold and to deliver it to Congress at Philadelphia. What he found on arrival in Havana on January 31, 1783, was that another ship, the USS Duc de Lauzun, was already in port on the same mission so Barry decided to escort her home. They left Havana on March 6, 1783. On the voyage to Philadelphia, the nation’s capital at that time, the Alliance and the Duc de Lauzun were spotted by three Royal Navy ships, the HMS Alarm, HMS Sibyl and HMS Tobago. A running battle ensued which ended with some 40 minutes of close in fighting, which finally forced the British ships to withdraw. Captain Vashon, commander of the HMS Sybil, is recorded as saying “he had never seen a ship so ably fought as the Alliance.” Captain Vashon is further quoted as saying of Barry, “every quality of a great commander was brought out with extraordinary brilliancy”.

While the battle was raging, and unknown to all of the combatants, The Treaty of Paris ending the American War of Independence was signed on February 3, 1783. In that battle the Alliance fired the last shot of the Ameri-can Revolutionary War.

On June 20, 1783, after picking up a cargo of tobacco for shipment to Europe, the Alliance struck a rock in Chesapeake Bay. Since the necessary repairs would be quite expensive and Congress had no funds available for repairs the Alliance was auctioned off by order of Congress in 1785 for $7,700. She was converted to a cargo ship and sailed to China, one of the earliest ships in the China Trade. Her final master was Thomas Read. As her master during her first merchant voyage Read took her to China by a new route through the Dutch East Indies and the Solomon Islands. Read and the Alliance departed Philadelphia in June 1787 and arrived at Canton on December 22 of that year. While passing through the Carolines on the outward voyage Captain Read found two islands that were not on his chart and named the first Morris, and the second, Alliance. At Canton he loaded the ship with tea, which he delivered back at Philadelphia on September 17, 1788, ending a record voyage.

No details of Alliance’s subsequent career have survived. However, when she was no longer seaworthy, the for-mer frigate was abandoned on the shore of Petty Island across the Delaware from Philadelphia. At low tide, some of her timbers could be seen in the sands there until her remaining hulk was destroyed during dredging operations in 1901.